25/01/2018 16:56

(Photo: Gilka Resende/FASE)

The conviction of former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, upheld by the 8th Chamber of the 4th Federal Appeals Court (TRF4) in a ludicrous trial in Porto Alegre, with no care even to simulate due process or produce suitable evidence, obliges us to reflect on what has become of democracy in Brazil. Many have already raised their voices to denounce the imminent overthrow of the principle of people’s sovereignty, with the consolidation of the 2016 coup through confined, illegitimate elections.

During President Dilma Roussef’s impeachment, several representatives of society’s most excluded sectors publicly criticized the hypothesis that democratic rule of law had been subverted. In fact, however, it was hard for residents of favelas and other areas impoverished by the system who suffer insecurity and police violence every day, with the systematic extermination of black youth, to even imagine that the state by which they are oppressed is either democratic or legal. While it may be the rule of law, it is not democratic. They perceive the state at the service of the monied classes and, above all, of their “god” the market, and the media that works at their behest.

The impeachment, and the brutal and systematic offensive to tear down rights that followed in its wake, unquestionably intensified the erosion of democracy in Brazil. But they did not inaugurate the post-democratic state. The tragic coincidence between the timing of Brazil’s redemocratization after the civil-military dictatorship – with the new 1988 Citizens’ Constitution – and the first cycle of neoliberalism in Brazil, under Presidents Fernando Collor, Itamar Franco and Fernando Henrique Cardoso, set very narrow limits for democracy to grow and take root. The 2008 economic crisis and the new international political situation – to say nothing of political blunders by Dilma Roussef during her second term – set a stage for neoliberalism to move back into the country, through anti-people “reforms” during Michel Temer’s de facto government.

Trial at the TRF-4 appeals court. (Photo: Sylvio Sirangelo/TRF4)

Brazil’s ruling classes, especially financial capital’s birds of prey (“the market”), have apparently lost their sense of limits. They behave as if the people were all fools and blind to contradictions between the hypocritical morality with which they convicted Lula and the lenience with which they handle the Congressional shield that keeps Temer and his hoaxes afloat, as he destroys labor rights, social security and other rights won in the 1988 Citizens’ Constitution.

“Now I’m realizing the difference between formal democracy and the democracy we live in. (…) But where is everyone equal before the law, if women are discriminated against? How can everyone be equal before the law when blacks are discriminated against, and Indians? Where is the equality?” asked former President Lula after his trial. The deep inequality underlying the structure of Brazilian society – which engenders the confrontation identified by Lula between formal and substantive forms of democracy – is now being grotesquely manipulated politically and legally based on the Court’s alleged application of the principle that all men and women are equal before the law.

The panel of appeals judges in Porto Alegre not only convicted former President Lula with no evidence of his guilt, invoking morality through a political judgement; they also undermine the legitimacy of their own power as magistrates, which can only grow out of absolute fidelity to law and to the unbending defense of citizens’ fundamental rights. The court’s political-partisan bias, under the ruse of “fighting corruption” and defending “public morals,” is an unequivocal usurpation of the people’s sovereignty.

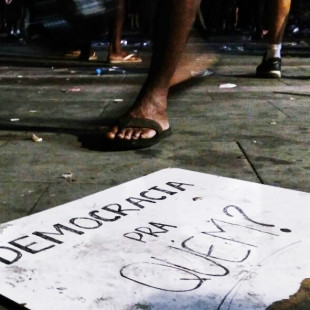

Protest in São Paulo. (Photo: Paulo Pinto/AGPT/ Public photos)

It also clearly raises the issue now dividing Brazilian society as its class struggle tends to radicalize: who shall exercise sovereignty in the state? The people, through an arduous process of winning back the democratic rule of law, or the usurping consortium of media oligarchs, courtroom guilds the and economic élites? It is very unlikely that people’s sovereignty will be reestablished in 2018 through another covenant of conciliation between big capital and the people’s movement. It will take a long struggle for the rights of the people’s classes to triumph.