31/08/2017 16:16

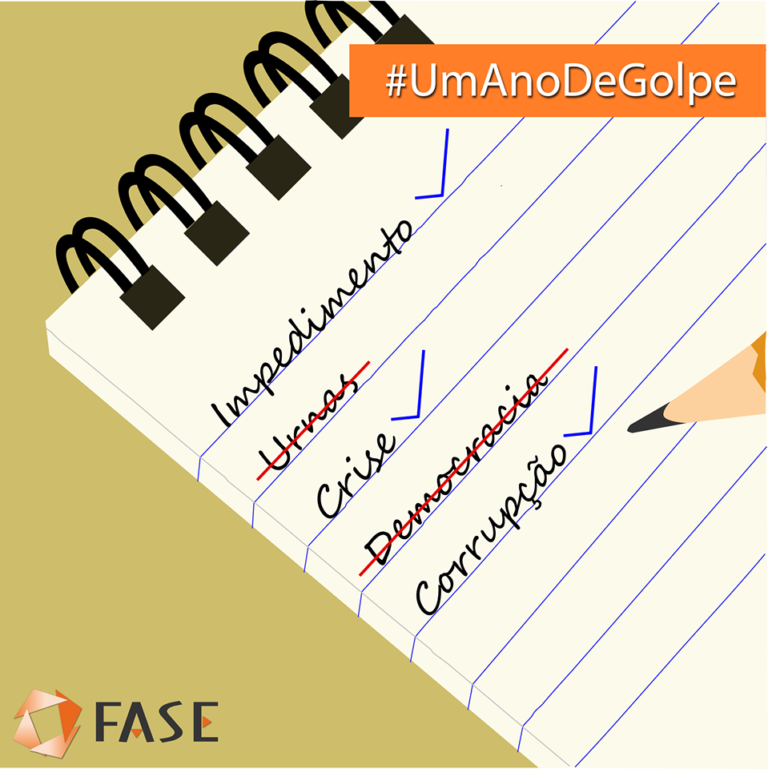

Just a year ago, Brazil’s Senate, in a 61-20 vote, approved the removal of Dilma Rousseff from her office as President, accused of impeachable fiscal offenses involving credit operations, a kind of “fiscal juggling” related to decrees thought to have led to spending beyond limits authorized by Congress. The first woman to have governed Brazil, re-elected to a second term with 54 million votes, was overthrown based on what many legal experts consider to be weak arguments. Michel Temer, who had already stood in as President since May 2016, was sworn into office. For many who had long criticized several dimensions of Brazil’s precarious democracy and human rights, the new administration was the illegitimate outcome of a coup d’état.

As we reflect on the background to that historic moment, we see complex factors behind the crisis. A “governability pact” that had held the country’s political system together since the 1988 Constitution had never broken down, even following the Presidential elections of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff. The myriad structural inequalities underlying Brazil’s very social formation had held firm, with its extreme concentration of political power and wealth in the hands of a few. Years of blatantly neoliberal policies and submission to the IMF in the 1990s both faithfully portrayed that logic.

As we reflect on the background to that historic moment, we see complex factors behind the crisis. A “governability pact” that had held the country’s political system together since the 1988 Constitution had never broken down, even following the Presidential elections of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff. The myriad structural inequalities underlying Brazil’s very social formation had held firm, with its extreme concentration of political power and wealth in the hands of a few. Years of blatantly neoliberal policies and submission to the IMF in the 1990s both faithfully portrayed that logic.

The election of progressive governments in Brazil did not put an end to neoliberal macroeconomic policies, despite the adoption of social policies contrary to neoliberal recipe books. Higher commodity prices, trade surpluses and their positive input to the federal budget enabled measures such as long-term raises to the minimum wage and funding for social programs such as the well-known Family Stipend. In a country where hunger and poverty go back centuries, such steps indeed brought major changes, but they integrated people through consumption, with no real change in most of their political roles as rights holders.

Underlying economic and political rules remained unchanged. Most of the public budget still goes to financial capital, through hikes in interest rates on the public debt and policies to subsidize sectors like agribusiness, despite the human rights violations and environment degradation they cause. With minor shifts in budget allocations, therefore, these governments managed to please both bankers and sectors of the poor. Despite ongoing criticism from the left, the governability pact held steady even through the international crisis of 2008, downplayed by the government as a “ripple.”

Agribusiness favored by boundless subsidies during PT governments. (Photo: Roosewelt Pinheiro/ABr)

That balance, however, was extremely fragile. The government’s insistence on big infrastructure and mining projects and on mega sporting events brought environmental, social, economic and cultural abuses that exposed the need for better public services in health, transportation and education, as well as an end to state violence through militarized police forces. Meanwhile, mainstream corporate media showed its own firepower, by criminalizing and manipulating protest demonstrations.

Falling commodity prices started pressuring the budget, and persecution by sectors of the court system and the media heated up the 2014 presidential election campaign, which former president Dilma won by a small margin of votes. The defeated coalition, however, gave no respite and attacked her administration with the support of the corporate media. The PT government suffered the consequences of never having dealt with the country’s media monopoly.

Coup brings new government and election results are ignored. (Photo: ABr)

President Dilma came under misogynistic fire and growing attacks by an increasingly conservative opposition. To calm down the “market” (banks and investors), the government embraced the macroeconomic policies promised by the candidate it had just defeated in the elections, thus weakening its own already waning social base. With little support from “the streets” and a minority in Congress, attacked by the corporate media and betrayed by the conservatives in its own coalition, the government spiraled into absolute crisis.

Police and public prosecutors’ investigations into corruption, even as they came to compromise broader swathes of politicians, went on unfettered during Dilma’s administration. This vexed everyone trying to avoid being sentenced and imprisoned, and further fueled procedures to impeach and remove her from office. Since then, both progress made during the PT governments and long-standing conquests such as the 1930s Labor Legislation (CLT) have been overturned. The approval of Constitutional Amendment 95/2016, which put a ceiling on public spending for 20 years, means less money for the Family Stipend, the cancellation of open hiring competitions for public servants and cutbacks in education, health, housing and other areas.

During this time of ongoing abuses, even amid uncertainties and growing violence in low-income territories, communities, organizations and social movements continue to resist and defend life, in the cities, countryside and forests.